THE GREAT ONE!

A reminder of the all or nothing legend that was Jackie Gleason. オール・オア・ナッシングのレジェンド、ジャッキー・グリーソンを思い出させます。

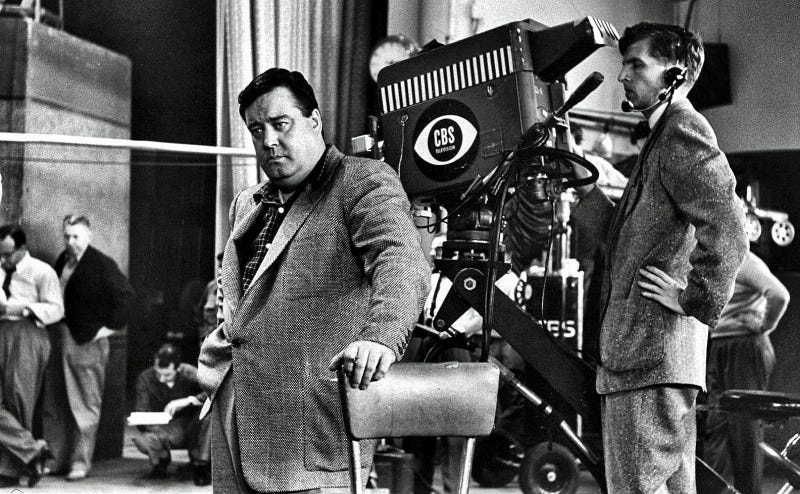

In the mid-1950s, actor/comedian Jackie Gleason yearned for a secluded hang-out spot for his all-night parties and amorous liaisons, far removed from Manhattan’s predatory gossip columnists. (As the highest-paid and most popular television star of his time, Gleason made for good copy. He was a high-living, hard-drinking clotheshorse who reveled in his image as a free-spending libertine.) So, he built a house in the country: a circular mansion with two swimming pools and four bars, fashioned from Carrara marble and thousands of pieces of hardwood curved by hand. Gleason’s UFO-inspired Spaceship, as it came to be known, mirrored the man: large and round, luxurious and improbable, it should have been too much, but in fact it was a harmonious marriage of money and good taste. While the Spaceship became an icon of mid-20th Century architecture, Gleason himself has faded from popular consciousness, an inevitable consequence of the march of time, changing tastes, and a media landscape that bombards us with new faces but rarely provides us with genuine stars, much less artistic geniuses. Gleason was both.

One of the pioneers and possibly the greatest practitioner of TV sketch comedy, Jackie Gleason created characters both poignant and preposterous for his weekly variety shows. His gallery of comic misery included The Poor Soul, a gentle man whose efforts to practice kindness inevitably ended with his wrongful arrest; Reginald Van Gleason III, a self-parody of his creator’s hubris, who despite being rich and successful was forever an outsider; and, of course, bombastic bus driver Ralph Kramden, the ever-hopeful, eternally damned protagonist of Gleason’s masterpiece, The Honeymooners.

Mirroring Gleason’s own impoverished childhood, The Honeymooners served up the bleakest glimpse of working-class frustration ever brought to a mass audience under the guise of “comedy.” Every episode followed the same basic pattern: Ralph attempts to better his circumstances and is humiliated for his efforts. Sympathetic but unyielding wife Alice and genial upstairs neighbors Ed and Trixie Norton, the frequent targets of Ralph’s vainglorious boasting and bullying, ultimately win the day by accepting the fact that they are trapped in a societal rat cage. Like another apoplectic loser, Daffy Duck, Ralph is continually undone by his pride and bottomless capacity for pointless rage. Case in point, the episode “Please Leave the Premises,” in which a minor rent increase compels Ralph to go on a rent strike “to teach that Johnson a lesson.” The landlord retaliates by turning off the heat, water, and electricity. Ralph refuses to budge. By the end of the episode the Kramdens are out on the street in the middle of a snowstorm, at which point Ralph finally gives in – not, he claims, because he was wrong, but because he’s worried about Alice’s health. Anyone who’s found themselves caught up in an ever-escalating spiral of madness provoked by a minor point of honor can relate.

In real life, Gleason’s temperament veered between manic Ralph Kramden and icy Minnesota Fats, the pool shark he portrayed in The Hustler. (Gleason performed his own trick shots for the film and earned an Academy Award nomination for his understated performance.) His biographers either celebrate or castigate the man. To James Bacon, author of How Sweet It Is, Gleason was a heroic figure who led a life ordinary mortals can only dream of. To William A. Henry, author of the well-researched but woefully judgmental The Great One, Gleason was a mercurial egomaniac who enjoyed the company of what the writer calls “fallen women.” (Henry’s book was published in 1992, five years after Gleason’s death, when alcoholism was still viewed as a moral failing and readers were expected to be shocked to learn that a successful comedian with an addictive personality was prone to fits of anger and bouts of depression.) It’s clear that, like many men of his generation, Gleason drank heavily to silence the shrieking in his head brought on by a childhood rife with poverty and abuse. But unlike many, Gleason was able to draw on his pain to create art that resonated with tens of millions of people. To make that art he had to fight the networks for creative control and press the people who worked for him to meet his exacting standards, both things guaranteed to make you enemies in show business.

Viewed from the perspective of 2024’s merciless social media panopticon, where displays of empathy are considered signs of weakness and kissing the corporate sphincter is saintly behavior, Gleason may seem a hopeless relic of the 20th Century. Big, bold, brash, yet painfully sensitive, he made himself adored, then tested the limits of that adoration by taking on roles that were increasingly dark and complex. Were these expressions of the inner man? Or was Gleason really the light-hearted party boy he pretended to be? Does it even matter? Gleason the man is long dead, but his best work –The Honeymooners – still resonates today, a sublime portrait of desperation that illuminates the beauty and absurdity of the human condition. Like Gleason’s improbably beautiful Spaceship, it is a monument to the potent combination of craftsmanship, ambition, and suffering that often fuels great art.

Kurt Sayenga

Three links to Jackie’s finest work